Tablet monument by Tiffany Studios

Monolithic, stylized and composed of granite from the firm’s own quarry, the tablet memorial above embodies a number of themes in Tiffany Studios’ funerary art. As a designer, Tiffany sought to ally himself with the aesthetic movement. Throughout his career he identified as a fine artist, a business man who pursued beauty and a synthesizer of the aesthetic themes that interested him. To understand the funerary art of Tiffany Studios it’s useful to delve into some of the themes and events that inspired their designs. Subtle as they are, for one example, the firm’s stone memorials typically incorporate the kinds of references to “exotic” cultures Tiffany employed in his interiors. Arguably chief among these was the influence of Japanese art and design, yet he and his designers also returned to the achievements of Romanesque and Byzantine artists again and again.

Although Louis Comfort Tiffany was already an important designer in New York and known in Paris before 1893, the Romanesque-Byzantine Chapel his firm exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago exposed his work to a broader American audience. His Paris representative, the influential gallery owner and publisher Siegfried Bing, is credited with persuading him to create this exhibit. At this time in American history there was an ongoing surge in the construction of houses of worship, with a concomitant need for ecclesiastical items such as vestments, altars and colored windows. Up to 1.4 million people viewed the Tiffany Chapel and the number of commissions Tiffany Studios received for such items increased dramatically thereafter.

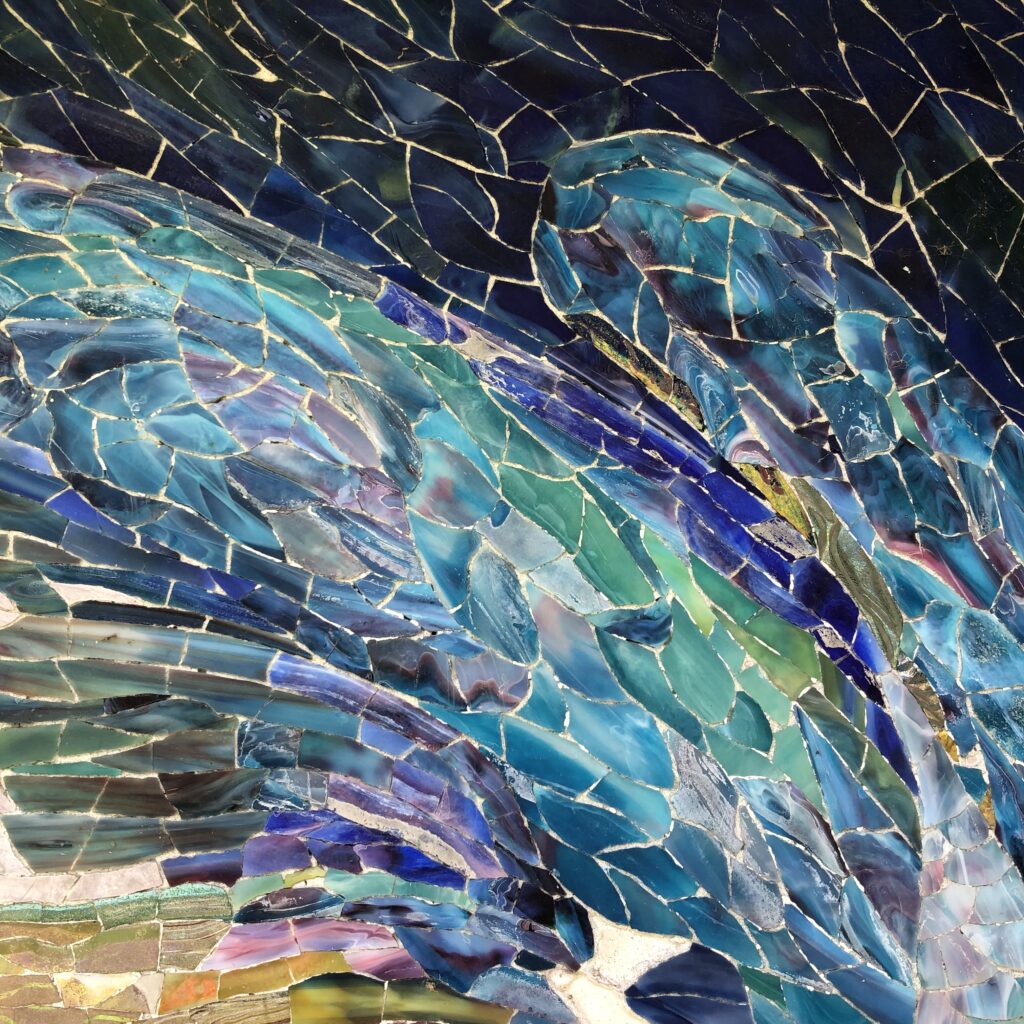

Specific itineraries for Tiffany’s travels have not been discovered in research done to date, but he clearly found inspiration in the Byzantine era mosaics of Ravenna and Rome. This is evidenced by his collection of photographs, his books and many of the artifacts he designed. The effects of light on glass to be found among them are central to Tiffany’s most powerful achievements. One of the chief qualities of mosaic as a decorative element is its effect of casting light in many directions, in a word, sparkling. This is a result of the practice of angling individual tesserae and sectiliae so they can catch and reflect light, a practice which Tiffany derived from precedents he found in important churches of the Byzantine Empire.

The Tiffany Chapel was designed with a recessed area separated from the sanctuary space by a screen of columns. Within it a bronze and stone baptismal font stood in front of a large stained glass window depicting lilies framed within a similar colonnade. This window is an example of a design that illustrates the form, shadows, lights and darks of its subject via a “mosaic” made up solely of different pieces and layers of colored glass. The ultimate goal of Tiffany and his rival LaFarge in their windows was to achieve figural effects without the use of figurally painted elements.

Today, the key components of the Chapel are displayed at the Morse Museum in Winter Park, Florida where a great many of Tiffany’s most important works are held. After about 1916 it was installed by Tiffany at Laurelton Hall, his estate on Long Island, having been sealed up in the crypt of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine once Ralph Adams Cram took over as architect of that project. In 1919 Tiffany established the Tiffany Foundation to support arts education at Laurelton Hall, and provided an endowment with the idea that his collections, house and Chapel would become his cultural legacy.

With the success of the Columbian Exposition, Tiffany Studios established a separate Ecclesiastical Department to handle the large volume of memorial work the firm needed to produce. Their products ranged from humble ledger stones to grand mausolea. Marketing materials for funerary art offered by Tiffany Studios to prospective patrons include their concisely titled 1914 brochure, Mausoleums. The historic precedents cited in it help to trace the aesthetic origins of the eighteen or twenty mausolea they produced. Some of the Tiffany buildings are remarkably precise recreations of properly detailed Ionic or Doric temples. Others are rather unconventional like the George M. Cohan mausoleum. A particularly quizzical one appears to be an adaptation of a Mamluk tomb from the environs of Cairo, an area Tiffany visited during one of his lengthy trips to paint in foreign locations. His painting On the Way Between Old and New Cairo showing Mamluk tombs in the background is held by the Brooklyn Museum. One of the mausolea depicted seems to be the model for the above mentioned tomb.

Mausoleums indicates that the monument commissioned by railroad executive Hamilton McKown Twombly in the 1890’s derives from both the two story Nereid Monument of Lycian Xanthos (now in Turkey) held at the British Museum, and the “tomb” of Zechariah in Jerusalem. Like the latter, the memorial is a cenotaph in the Ionic order, although the author of the 1914 pamphlet seems to have been unaware that there are burial chambers beneath and around it. Coffman makes the astute observation that the individual grave markers surrounding it have an anthemion design that is more horizontal than its classical precedents, as though the motif had been compressed. Given Tiffany’s contribution to the Art Nouveau movement, Coffman convincingly suggests that this transformation is an example of this late 19th and early 20th century style.

As mentioned above, the aim behind the development of Tiffany favrile glass was to achieve painterly effects by simply using pieces of light, medium and dark glass of varying hues, entirely eschewing the use of vitrifiable pigment. Tiffany had started experimenting with glass early in his career, ultimately building expansive glass furnaces in Corona Queens. There he was able to maintain a cadre of artisans who fabricated the many hues, textures and mixes of glass used in the windows. They also played with form and integrated color in the extraordinarily imaginative glass tabletop items for which the Studios are so famous. Reviewing flower-shaped vases and punchbowls clearly inspired by cephalopods, one can readily see in their flowing forms Tiffany’s contribution to Art Nouveau.

Aside from the lily window of the Chapel’s baptistery, a number of Tiffany’s other windows achieve the lofty aim of depicting form, light and shade without the use of painted glass. One of the methods that contributed to this end was Tiffany’s patented plating method which incorporated airspace between the layers of glass. This enabled the artisans to create a particular glowing effect, perhaps because light passing through the colored glass also had space to reflect back and forth within the airspaces in a kind of reverberating effect. The 1914 monograph, The Art Work of Louis Comfort Tiffany, written by Charles deKay and evidently based on direct comments by Tiffany himself, contains the insight that the first stained glass windows derived from the ancient craft of glass mosaic. One can imagine artisans of the era handling brilliantly hued translucent glass tesserae intended to adorn walls and domes and how they considered in what way they might be mounted so that, rather than being limited to reflecting light from the face of a solid surface, they could transmit it and allow it to transform an interior space with colored light.

Where art glass windows held the advantage of transmitting light, glass wall mosaics could be endowed with greater benefits of painterliness. It was in the latter that Tiffany was able to combine the subtlety of shading and modeling with what he believed to be permanence. Any of the thousands of proprietary Tiffany colors could be combined to form pictorial results entirely and solely with Tiffany glass. No detail was too small since glass could be shaped virtually to any size desired and any color could be fabricated. As well, imperfections in the handmade surface would result in a desirable random scattering of light whether the tesserae and sectiliae were intended to be flush to one another or angled.

Unfortunately the Swan aedicule at Woodlawn Cemetery, as one example, did not provide enough cover for the joyful Art Nouveau mosaic angel it was designed to protect. The brochure Glass Mosaic of 1896 states that outdoor mosaics were affixed using hydraulic or oleaginous cement. Although the glass elements might have been “practically indestructible except by direct violence,” the original Tiffany cement was not. In contrast, the indoor setting along with considered conservation have preserved and protected the brilliant use of color and artisanry of the astounding Dream Garden mosaic in Philadelphia.

A related monument in Upstate New York was given the curious notation in the Tiffany Studios inventory of “Circular Temple,” but its small scale suggests that it is more of a shrine. Incorporating architecture, bronze work and mosaic, it showcases the many claims to expertise that the 1922 brochure Memorials In Glass and Stone vaunts. The technical capabilities of the Ecclesiastical Department were supported by stone carvers at the Tiffany granite quarry in Cohasset, MA, the Tiffany Glass Furnaces, the decorative metal works and Tiffany foundry, all in Corona, Queens. Tiffany brochures also state that the company could produce painted memorial tablets, intricate needlework and frescoes. Examples of all of these products survive, although they are dispersed among many collections, institutions and cemetery sites. However the Upstate mosaic endured a fate similar to that of the Swan aedicule’s: it was removed and replaced with a modern reinterpretation and even the favrile glass tesserae are lost.

Celtic ornamentation, a relatively new archaeological discovery in Tiffany’s era, appears again and again in his work. The Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones was one of many sources upon which Tiffany drew. Specific motifs which appear in this reference are virtually recreated in monuments, millwork, needlework, et al. Jones’s description of the decorative motifs from this culture note explicitly that the interlocking cords and bands which form “knots” entirely lack foliate elements, which classical or Byzantine ornamentation would typically have included. Aside from Tiffany’s discomfort with the direct use of historicism in design, one might conclude that for him the continuous flow found in Celtic knot motifs would have shared a similarity with the movement of the malleable glass with which he was so successful, and that it too is at least indirectly related to the Art Nouveau glass objects Tiffany created.

From a young age Tiffany collected Asian artworks and artifacts. It’s believed that his relationship with Siegfried Bing’s gallery began when he was quite young, possibly through Edward C. Moore, chief of design at Tiffany & Co., who purchased Japanese artifacts there for Tiffany’s father’s business. Tiffany himself is said to have held the largest collection of Japanese swords in the world. That samurai swords were kept in arcing black lacquer sheaths is quite familiar, but less known is that the samurai would have slipped a metal guard over the blade to protect the hand while the sword was in use. These guards, called tsuba, came in an enormous variety of shapes and were decorated with a wide range of motifs. Tiffany purchased tsuba by the barrel and used them frequently in his decorative work.

The shapes of tsuba cut in half horizontally can be detected in the silhouettes of many Tiffany stone memorials. While the overall profile often derives from sword guards, a number of other ornamental influences might be incorporated into the carving such as Christian apocalyptic symbols, flowing Celtic ornament and even the symmetrical composition of the pair of decorated teak wine casks which flanked the fireplace in Tiffany’s New York Breakfast Room. The synthesis of many inspirations, evident throughout Tiffany’s approach to design, is remarkable for its harmony. While the stone monuments have none of the elan of the stained glass work, they embody a unique combination of sober form and expansive vision.

In the text of Out of Door Memorials, an 1898 brochure, one of the first historical precedents cited is a shaft which the Biblical Jacob placed over the grave of his wife Rachel, located near Bethlehem. Today the rounded form of this memorial, just detectable beneath numerous protective coverings, reveals itself to be another shape Tiffany liked to employ. As tsuba often had filleted edges to protect the hand from being cut by metal, the roundedness of Rachel’s shaft was likewise echoed in stone memorials by Tiffany Studios. While the Studios’ memorials often referenced this historical precedent in their overall sugarloaf-like shape, at times it also made its appearance in monuments based on tsuba, which for Tiffany typically had parallel front and back surfaces with crisp edges. (The monument Tiffany designed for the grave of his parents is one example). The influence of Rachel’s shaft often can be found in rounded edges and sloped faces, giving monuments a softened appearance.

Bronze work produced by the Studios’ own decorative metal shop and foundry is less common than their stone memorials. In some rare cases it’s combined with granite as a commemorative sheath covering part of the monument. Tiffany Studios also created bronze memorial tablets to be hung on the walls of churches, sometimes with a bas relief image related to the person commemorated. Bronze ornamentation was used to frame a sarcophagus or the slab of a crypt. In certain instances the memorial’s design might include a finely sculpted bronze object such as a tripod or oil lamp.

The Veterans’ Room and Library at the Park Avenue Armory is an early work by Tiffany and his Associated Artists (Samuel Colman, Lockwood de Forest and Candace Wheeler). The stained glass windows facing both Park Avenue and East 67th St. are entirely geometric in design, whereas exotic motifs from North Africa, Spain and Celtic manuscripts enter the mix of the interior stone work and millwork quite harmoniously. Not only is this a rare, surviving Associated Artists interior (with the exception of the textiles produced by Wheeler), it is also a remarkable example of the sophisticated color mixing which Tiffany could produce. Photographs of lost Tiffany interiors, being black and white, cannot convey the subtlety of the mixture of elements and hues involved. It’s only when a surviving rendering can be compared to a photograph that we may begin to understand the overall effect with which Tiffany imbued it. In this regard, certain mausoleum interiors retain enough original elements such as colored marble, mosaics and glass, that we might have an idea of the color schemes employed.

Ralph Adams Cram, with his polemics against opalescent glass, was one factor in putting an end to the fashion for Tiffany’s creations. Ironically, Tiffany had no bias against using medieval design motifs, but did repudiate historicism per se. The story of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine is emblematic of the dispute. Upon the death of architect George L. Heins, Heins & LaFarge’s Romanesque-Byzantine inspired church design was terminated. A generous patron had previously donated the Tiffany Chapel to the cathedral. It was installed in the crypt and used for services while the main sanctuary was being constructed. In order to proceed following Heins’s death, the church architectural committee awarded the commission for completing the cathedral to Cram, who promptly developed a Gothic Revival design. The Chapel was sealed and the trend for Romanesque-Byzantine inspired architecture and decoration rapidly diminished in popularity.

One source tells us that Tiffany intended to be entombed in the Chapel which he had reassembled in one of the outbuildings at Laurelton Hall, laboratory for so many of his experiments in architecture, landscape and the decorative arts. This property, which included elaborate gardens, its own heating and pumping station, and a mansion decidedly original in its design, was reorganized towards the end of Tiffany’s life as a testament to his contributions as an artist. The Tiffany Foundation was established about fourteen years before his death so that artists invited to paint there could take advantage of the setting, its collections and, during his life, his own presence. One of the fellows in 1930 was Hugh F. McKean who, in partnership with his wife Jeannette, saved as many artifacts as possible from Laurelton Hall after the fire that devastated it in 1957. It is due to their generosity and vision that the Tiffany Chapel and baptistery can now be viewed in person at Winter Park.

SOURCES:

Burke, Doreen Bulger, et al.; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, History (Timeline), [New York], n. d., consulted 10-25-23.

www.stjohndivine.org/about

Coffman, Eileen Wilson, “Silent Sentinels.” Thesis, Arizona State University, 1995.

Freylinghuysen, Alice Cooney, et al.; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Laurelton

Hall. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Freylinghuysen, Alice Cooney, Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum. The

Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (reprint), [New York], Summer, 1998.

Koch, Robert, Rebel in Glass. New York, Crown Publishers, 1982.

Murray, Stephen, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Media Center for Art

History and Historic Preservation, consulted 10-25-23. www.projects.mcah.columbia.edu

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co., Glass Mosaic. [New York] n.p., 1896.

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co., Memorial Windows. [New York] n.p., 1896.

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co., Out of Door Memorials. [New York] n.p.,

1898.

Tiffany, Louis C., Color and Its Kinship to Sound, The Art World, May, 1917, 142.

Tiffany Studios. Mausoleums. Baltimore and New York: Munder-Thompson

Press, 1914.

Tiffany Studios. Memorials in Glass and Stone. [New York] n.p., 1913.

Woodlawn Cemetery records. Located in the Dept. of Drawings & Archives,

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.