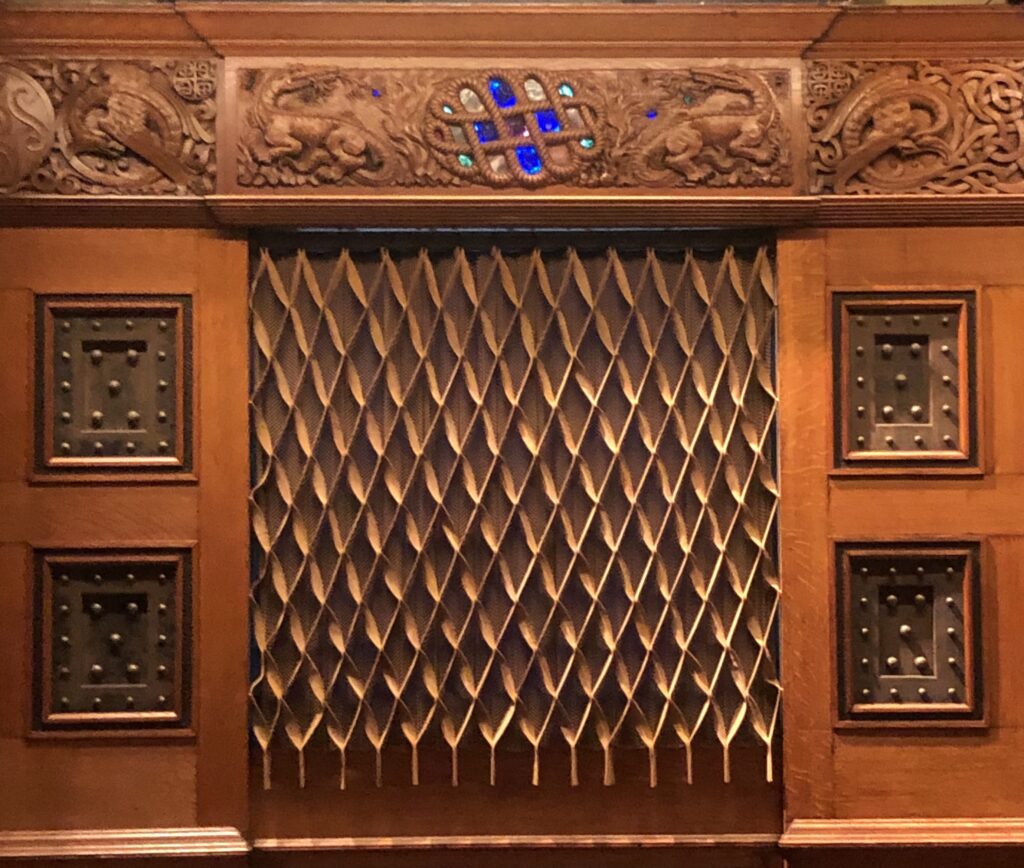

Tiffany favrile glass from a mausoleum interior

Given his driven personality, is there any wonder that Louis Comfort Tiffany applied radical rethinking to every design problem he faced, even to funerary monuments? He came of age as an artist, artisan and designer during a period of extraordinary cultural richness in the United States. Tiffany was in his fourth year when London’s Great Exhibition excited a fresh approach to the quality of design in Britain. He was six when Commodore Matthew C. Perry negotiated the Treaty of Kanagawa, opening Japan to trade with Western countries for the first time in more than two hundred years. At the age of twenty-eight he exhibited paintings at the Philadelphia Centennial International Exposition, a world’s fair which showed Americans a fresh way to conceive of design and the arts in this country. All of this took place against a backdrop of experimentation among architects in the United States and England. They sought to develop an appropriate contemporary idiom in their field by synthesizing diverse aspects of historical styles, not always with happy results. Over a career spanning more than fifty years, Tiffany left a unique imprint on the decorative arts in his native country. If there is a single thread to follow, it would be that his achievements can be understood more deeply when considered in contrast with more conventional artifacts produced by American creative practitioners of his time.

Rejecting the anticipated path that he would enter his father’s famous jewelry business, Tiffany’s first pursuit was as an artist, painting in watercolor and oil. Of special note are his scenes of North Africa which display accurate draftsmanship, careful rendering and a keen eye for detail. This part of his career manifested in his later endeavors thematically in that he incorporated so-called exotic motifs from Egypt, Morocco and Tangiers into his design work. It also provided the practical skills required for rendering designs of colored windows and interiors. Although not a copyist, features found in Japanese art also occur in his paintings: his lifelong attraction to nature and flowers in particular dovetailed with the influence of such elements in Japanese woodblocks, ceramics, textiles, et al. without mimicking them stylistically.

The use of the word “artisan” above refers specifically to Tiffany’s achievements in creating colored and textured glass. Early in his career this was achieved through his work with existing glass houses. Later on, Tiffany established his own glass works and furnaces. Colored windows and glass mosaics were conceived by the firm as being closely related. By developing proprietary formulas for coloring glass and techniques for providing it with strength and texture, Tiffany Studios was able to create an almost infinite palette of hues with associated tonal value variations. Using this palette form, void, shadow and most particularly, light effects were all possible whether a translucent image was to be produced for a window or an opaque one for a mosaic. To gaze at the tesserae and sectiliae of the Metropolitan Museum’s wall fountain is to become lost in a landscape far beyond the edge of the basin. To view its Autumn Landscape window is virtually to experience the movement of a cascade and the dappled shadows to be found under birch trees.

As a designer, Tiffany carefully incorporated components from particular historical periods and styles into his interiors. Certain cultures appear again and again throughout his career: Islamic art and architecture; Indian carvings; Japanese textiles, papers and sword guards; Byzantine or Medieval Italian mosaics and ecclesiastical design; Celtic carvings and illuminated manuscripts. He was following his own interests, always with the aim of synthesizing particular types of motifs into what he believed would be an original, unified American approach. Nowhere was this synthesis more evident than at Laurelton Hall, Tiffany’s Long Island estate, which for decades served as his laboratory for experiments in landscape, architecture and the decorative arts.

The degree to which his synthesis of existing decorative elements achieves originality can be traced to philosophies of design which influenced Tiffany’s approach. The English Arts and Crafts movement that followed the Great Exhibition of 1851 resulted in the attention to the quality of materials and construction evident in everything his companies produced. The Aesthetic movement provided a differing but complementary philosophical basis. To sum up a complex movement simply, in Aestheticism the human sensory response was given preeminence over the formal or didactic aims which were more prevalent in the Victorian era. It led to the idea that the decorative arts could be equal to the fine arts such that designers conceived and presented their work as specifically “artistic.” These influences are central to Tiffany’s approach, as all of his work is intended to be artistic first and foremost, supported by excellent artisanry and the best “modern” materials. The “fusion of the best modern spirit with the assimilated spirit of the best mediaeval [sic] creations” is a statement that begins to sum up the enormous output of Tiffany’s career. Nonetheless, his goal would have been to create something fresh and American rather than copy historical precedents.

It bears noting that the amalgam of Arts and Crafts, Aestheticism and Japanese influences in Louis Comfort Tiffany’s work allied him with other artists and designers of the 1880’s. Because of their shared interests, a number of commonalities appear in their work, notably the focus on specific effects, decorated surfaces and graphic boldness heavily influenced by the arts of Japan. These practitioners, brought together by art dealer Siegfried Bing at his gallery, Le Salon de l’ Art Nouveau, are considered to be the founders of the movement.

Funerary art created by the Tiffany Studios, no less than their interiors and other works, when seen in relation to art and artifacts typical of his contemporaries, is astonishingly fresh. Tiffany glass glows more intensely than other opalescent windows; Japanese-inspired tombstones appear as markers from a yet-to-be discovered culture; Tiffany mosaics achieve tonal and chromatic modulations previously only achieved in traditional painting. Even the far less innovative mausolea the firm produced stand out among the monuments which surround them so that they virtually find themselves. The artists and artisans of Tiffany Studios understood how powerful their craft could be and used their knowledge to infuse every artifact they created with great impact.

SOURCES:

Burke, Doreen Bulger, et al.; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, History (Timeline), [New York], n. d., consulted 10-25-23.

www.stjohndivine.org/about

Coffman, Eileen Wilson, “Silent Sentinels.” Thesis, Arizona State University, 1995.

Freylinghuysen, Alice Cooney, et al.; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Laurelton

Hall. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Freylinghuysen, Alice Cooney, Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum. The

Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (reprint), [New York], Summer, 1998.

Koch, Robert, Rebel in Glass. New York, Crown Publishers, 1982.

Murray, Stephen, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Media Center for Art

History and Historic Preservation, consulted 10-25-23. www.projects.mcah.columbia.edu

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co., Glass Mosaic. [New York] n.p., 1896.

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co., Memorial Windows. [New York] n.p., 1896.

Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co., Out of Door Memorials. [New York] n.p.,

1898.

Tiffany, Louis C., Color and Its Kinship to Sound, The Art World, May, 1917, 142.

Tiffany Studios. Mausoleums. Baltimore and New York: Munder-Thompson

Press, 1914.

Tiffany Studios. Memorials in Glass and Stone. [New York] n.p., 1913.

Woodlawn Cemetery records. Located in the Dept. of Drawings & Archives,

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.