Photo by Cohen-Rose, Sandra and Rose, Colin, “Art Deco architecture in Havana,” 27 March, 2013. https://flickr.com/photos/73416633@N00/8880495939 ; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Havana_Art_Deco_(8880495939).jpg

Determining the date of death lies in murky territory. Nonetheless it holds the distinction, unusual for a style of design, of having a definite date of birth: Art Deco officially began in April of 1925 with the Exposition Internationale des Art Decoratifs et Industriels in Paris, but in fact its origins precede World War I. It has extensive roots, the first being French competition with the success of Germany’s Deutsche Werkbund fifteen years earlier at the Salon d’Automne of 1910. The sleek, aerodynamic forms architect Erich Mendelsohn developed in the late teens and early twenties lent their lines to streamlined designs created in the United States in the 1930’s. We find influences from Egyptian art and architecture, African sculpture, Cubism, Native American cultures and many regional variations, to name only a few. It’s in part for this reason that we know what Art Deco is when we see it, but even design critics have a hard time defining it.

The Exposition, following World War I, both caught and sparked the spirit of a new era. People were disillusioned with the political order that had led to the war. The idiom of classic design that prevailed before 1914 was associated with regimes that had caused the War’s pervasive devastation. Economies, cultures and governments were in great flux, with a concomitant worldwide sense of anxiety. More money was available to a broader range of people, at least in major cities like New York. And women were becoming increasingly important in markets across the world. Art Deco is about change and commerce because people were looking for expressions of a different kind of culture and could pay for the kind of escape that new products, new images and travel could provide. It is intentionally seductive and communicative, its forms both beautiful and easy to read.

Because of the multiple influences, the length of time the movement endured and the international dispersal of the style, it’s hard to pinpoint a specific set of criteria for Art Deco. Even finding a name for it leads to confusion. It’s first phase, with the 1925 Exposition, is generally known simply as Art Deco. Streamlining comes in after American designers start to make it their own. Sometimes called “Art Moderne,” this branch was heavily influenced by industrial design of the period, with a particular emphasis on the concept of expressing speed or motion linked with serenity. The 1939 New York World’s Fair represented a culmination of streamlining whose simplicity foreshadowed the asceticism that orthodox Modernism would manifest after the Second World War. Late in the Deco movement came a focus on simplified classicism which continued up to the end of the 1940’s, as many Federal projects attest in the United States.

Despite the international prominence of American architects like Louis Sullivan and his protégé Frank Lloyd Wright, Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover determined that the U.S. did not have sufficient resources to launch a fully modern installation at the 1925 Exposition. Instead, he sent a delegation of eighty-seven experts accompanied by journalists and civilian visitors. These were electrified by what they found in Paris, sending reports back home which galvanized their compatriots. Businesses in New York brought the Exposition to the United States. F. Schumacher & Co. displayed an entire room designed in Art Deco style by Paris decorators and had the fashion designer Paul Poiret create a line of textiles. Sloane’s, Macy’s and Altmans all had lines of goods supplied by Paris fabricators. Even today the western addition to the Bloomingdales building on Third Ave. still sports its black Art Deco finish surface and fancy aluminum syncopated entrances.

We cannot overemphasize the role of commercialism in the movement found everywhere in the Deco era’s culture from architecture, music, fashion, all the way to travel. During the Exposition, the auto manufacturer Citroen transformed the Eiffel tower, symbol of 19th Century engineering prowess, into a giant advertisement which utilized the technology of hundreds of electric lights to accomplish its mercantile goal. As the twenties continued, buildings and interiors were routinely outlined with lights, extending their command of attention to twenty-four hours a day. Paralleling the overt use of modern technology, but a little later than the Exposition itself, was a subtle shift to repetition of form. This represented a move from the hand-crafted luxury goods vaunted at the Exposition to the industrial production of novel product lines that were designed to excite dissatisfaction with existing, still useful possessions. Streamlined forms made manufacturing items easier to machine and to afford.

The laser-focus on women’s consumption of goods preceded the Exposition, but with it reached a peak. Paris, of course, had long been known as the center of luxury fashion, but 1925 saw a culmination in the number of small shops, specializing in limited lines of highly crafted goods. These were displayed in such a way as to highlight one or two items aimed at a female customer. Coming on the heels of women’s participation in the workforce or running households in the absence of the men who were fighting in World War I, this marketing atmosphere took advantage of the economic changes that made women more apt to determine how to spend money than they had done before the war. This is the origin of the idea of the Flapper.

When we look at Art Deco architecture, interiors or furnishings we see stylized ornament and often graphics in the form of signage. The two are almost always highly legible, which served the commercial intentions of using design to advertise products sold in the buildings, or even the rental space they made available to the market. Ornament served to emphasize the form of an edifice or piece of furniture, but more so, the form of the building or object made the entire thing more noticeable, with an identifying silhouette on a skyline often used as a means of attracting attention.

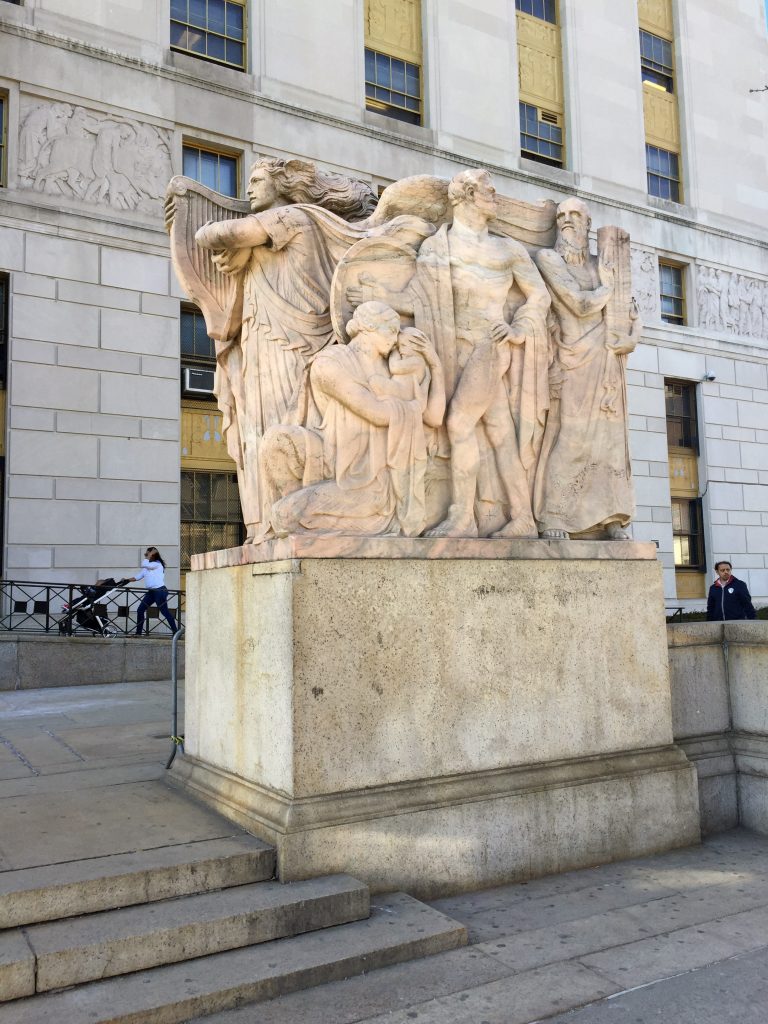

In the Bronx, the Grand Concourse assumed its Art Deco prominence after the IRT extended northward in 1933. The idea of the building silhouetted on the skyline was utilized here, although much more modestly than among Manhattan’s skyscrapers. After the Crash of 1929, development of the Grand Concourse continued despite the Great Depression. We see in civic buildings such as the Bronx General Post office or the Bronx County Courthouse the presence of Federal projects that continued the Art Deco idiom into its late, simplified classicist phase. It’s notable that Adolph Weinman’s Moses, one of his two sculptural groups at the east façade of the courthouse, holds not the Tablets of the Law, but their modern equivalent, a model of the courthouse itself. Even here the building reverberates with a kind of reminder or advertisement.

Of the myriad, one cultural influence on Art Deco bears particular mention: Egyptian Revival. In 1924 Raymond Hood designed the American Radiator Building in London which presaged the Art Deco movement with its exotic, quasi-Egyptian style and dramatic black and gold facades. Hood was later to collaborate with sculptor Charles Keck on the Deco-inspired Mori monument found at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, NY. Given that planning a large urban building takes many months, the London design came fast on the heels of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 by the British Howard Carter and his patron Lord Carnavon. The exotic, sophisticated items discovered in the tomb seduced imaginations of both designers and patrons around the world as Egyptian artifacts have many time throughout the centuries. Egyptian architecture particularly must have struck a chord in the period as so much of Art Deco architecture echoes the imposing elegance of its canted pylons, stylized papyriform columns and lofty hypostyle halls.

At Woodlawn we see the Egyptian Revival influence in James Gamble Rogers’s Straus and Hill tombs. The 1932 Hill monument less overtly expresses the style, but the braziers flanking its entrance have sphinxes’ faces surmounting their supports and the architects incorporated a stone in the interior called out as “Egyptian” granite. It is perhaps due to the sphinx motif that the tomb is considered an example of Egyptian Revival. The 1928 Straus monument derives from Egyptian “mastaba” tombs, which were typically used for aristocratic but non-royal entombments. The funeral barge carved by Lee Lawrie is a late addition as it replaces the sundial planned for that location in the original design. While it underscores the Egyptian theme and alludes to the death of Ida and her husband Isidor Straus in the sinking of the Titanic (Isidor is buried beneath it), inadvertently or not, it also hints at the importance of travel to the Art Deco era zeitgeist. Notably, both patron Percy Straus and architect Rogers were involved in the planning and design of the 1939 Fair.

The majority of Art Deco monuments at Woodlawn reflect an ascetic American take on the style. Generally speaking Art Deco forms emphasize expansion, either upward or outward, in an expression of progress, energy or movement. While the original 1925 French conception of the idiom bases architecture on a kind of monumental dynamism adorned with limited but rich ornament, American Art Deco in stone tends to be more sober. It utilizes the expansive forms but tends to limit decorative elements. Warren and Wetmore’s Stewart’s (later Bonwit Teller) Department Store comes to mind, and more so, Ely Jacques Kahn’s spare 1930 renovation of the interiors. Kahn was the architect of Woodlawn’s Rose mausoleum soon afterward in 1931. It’s also worth noting that the extravagant sculptural program of another Hood project, Rockefeller Center (ca. 1931-39), remains essentially within sight from ground level. Unlike the crowns of many deco skyscrapers that preceded it, here “ornament” used in a value-conscious manner is placed where people will encounter it.

Clearly the richness of luxurious Gilded Age mausolea was considered neither practical nor appropriate for a tomb after World War I. The elaborate classicism we see in the marble sculpture, custom bronze work and intricate mosaics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was out of style, and in an age of income taxes certainly less affordable. The Art Deco monuments at Woodlawn display a sophisticated use of simplified technique, emphasis on form rather than ornament, reduction in the number of details, and repetition rather than variation. This last again hinting at industrial methods of production. The typefaces used in inscriptions typically express what they need to with style, but mainly with great clarity. In metalwork, with art glass as its second, we see the clearest inventiveness and play. Bronze doors and grilles, almost always cast, are thus repeatable, so it seems that there is a focus on value here as well, even in the tombs of such notables as Philip Lehman designed by the master memorialist, William H. Deacy. We see, overall, similar forms to those used at the entrances to Art Moderne apartment buildings throughout the city, also suggesting the value-engineering of repeatable designs. In general interiors tend to be plain, with some notable exceptions, but never do we encounter the extravagance of precious marbles or naturalistic carving found in earlier tombs. In these monuments evidence appears of why the fortunes of the Piccirilli brothers declined following Attilio’s commission for the two experimental moderne glass reliefs which loomed above the entrances to the Italia Building on Fifth Avenue.

As an aside, the theme of historicism in the period cannot be ignored. As in any stylistic period, there were numerous themes both within and outside of Art Deco architecture. With the Guggenheim, Brenon and Salvatorelli tombs, we see how the influence of Gothic idiom was employed in varying ways. Dated ca. 1923, the Guggenheim tomb precedes the Exposition, but nonetheless attenuates the proportions of the elements in a way that remains compatible with Art Deco style. The Brenon tomb of 1926, built for a filmmaker of the silent era, suggests more of a set designer’s notion of medieval architecture rather than Deco. We must remember that this lot had included elaborate landscaping as part of its concept, so today we do not see it as originally intended. Of the three, the Salvatorelli mausoleum of 1931 displays the attenuation and emphasis on the vertical one would most expect to find in an Art Deco monument.

Conversely, in funerary design the Art Deco style could extend well beyond the generally accepted ending date of the era as seen in a number of tombs lining Park Avenue and elsewhere at Woodlawn, in some cases well in to the 1950’s. Monument suppliers such as H. K. Peacock or Adler’s Monument and Granite Works developed models which they kept in repertoire. Should a patron favor an existing mausoleum design, they were happy to adopt it for another family’s lot.

It is only in Paul Chalfin’s environment designed for attorney Samuel Untermyer at the very dawn of the Art Deco era that we come close to pre-World War I opulence. What is noteworthy in the design is the evolution of the concept, specifically as evidenced by a change in the form of the “shrine.” The lot itself is quite large, about 200 feet by 150 feet, with a total area of over 22,000 square feet. What the patron and architect chose to do, appropriate for a memorial to someone who loved gardens, was to create an overall landscape rather than place an individual monument on the site.

Since the lot occupies a gentle slope in Cliff Plot, the landscape consists of elements that retain soil and rise upwards in two general types, stairs and walls. Today one enters the site from Lawn Avenue and climbs up the main greensward toward the central fountain, but the original approach seems to have been via the small stair on the west which leads directly to Mr. Untermyer’s grave at the foot of the shrine. From there, in a rather direct but nonetheless elegant representation of the idea of familial descent, one can follow the landscaping down a series of broad steps defined by granite curbs encircling the ledger stones of Untermyer’s relatives, which extends past a patterned area of circular pavement circumscribed by a grand exedra with a high back acting as a retaining wall.

The bronze urn that serves as a fountain today was not drawn in the original plans from 1924, nor was the extraordinary Art Deco tower shrine that we see today. Chalfin’s initial drawings show the central area of pavement composed of various materials and incorporating a six-pointed star to reference Untermyer’s Jewish faith, but the later addition of the urn obscures this reference. We can only speculate that it had been sent down from Greystone well after the monument was completed, perhaps when Untermyer’s home and gardens were dismantled following his death in 1940. The long structure to the west, ultimately named the “Rhodendron Terrace,” was originally labeled “Reservoir” on the drawings, so it is plausible that a fountain had been planned for the site early on, intended to be finalized after completion.

The shrine began as a simple plinth adorned with a classical wreath and surmounted by a figural sculpture. But curiously some time after the 1925 opening of the Exposition, the current Art Deco treatment appeared in the architectural drawings which show the tower and its exuberant scalloped bronze roof as we see it today. What might have originated as a classically inspired landscape treatment for this grand site suddenly reads as an Art Deco environment. This is in part because the detailing of the stonework is generally neutral and in part because Art Deco absorbed a certain amount of classical design influence, particularly in its early days. What enhances the idea of an Art Deco approach is the powerful tension in the long, low steps that rise along with the grade of the land and the exaggerated height of the exedra’s back. These elements, as well as the steep wall of the Rhododendron Terrace and lofty shrine send the eye upwards, which is a classic Deco strategy.

Arguably the style died at the end of the 1930’s. In June of 1940, just months before the closing of the 1939 World’s Fair, France surrendered to the German armed forces which had occupied Paris. The apogee of French Art Deco design, the oceanliner Normandie, renamed the USS Lafayette after expropriation by the U.S. Navy, burned and sank in the Hudson River in 1942. The famous Perisphere and Trilon, considered by their architects to be the basilica and campanile of the fair, were demolished, the steel that composed their structures transformed into war materials.

Opening image: Catalina Lasa tomb by Rene Lalique. Photo by Cohen-Rose, Sandra and Rose, Colin, “Art Deco architecture in Havana,” 27 March, 2013. https://flickr.com/photos/73416633@N00/8880495939 ; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Havana_Art_Deco_(8880495939).jpg

Sources:

Benton, Charlotte, ed., Art Deco 1910-1939, V & A Publishing, London, 2015.

Beyer, Patricia, Art Deco Architecture: Design, Decoration and Detail from the Twenties and Thirties, Harry N Abrams Inc; 1992.

Breeze, Carla, Art Deco: Modernistic Architecture and Regionalism, W. W. Norton & Company, 2003.

Lowe, David Garrand, Art Deco New York, Watson-Guptill, 2004.

Robins, Anthony W., New York Art Deco: A Guide to Gotham’s Jazz Age Architecture, Excelsior Editions, 2017.

Woodlawn Cemetery records, 1863-1999, Drawings and Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.