Kyoto, 1863. Picture three human heads on wooden pikes, silhouetted against the brilliant white of an overcast sky, lofted above the Kamo River for all passersby to see. Placards enumerating their crimes are set up alongside this grisly tableau. The nine men who mounted them there considered their owners to be criminals. They were the heads of the first three Ashikaga Shoguns, Takauji (d. 1358), Yoshiakira (d. 1367) and even the creator of Kinkaku-ji, Yoshimitsu (d. 1408). Their supposed crimes, however, had occurred more than 400 years earlier.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s magnificent temple-“Ashikaga Yoshimitsu Admiring the Golden Pavilion LACMA M.2007.152.67” by Fæ is licensed under CC BY 2.0

For hundreds of years all fifteen Ashikaga Shoguns had been entombed in effigy in the Reikō-den at Toji Temple, just south of the original site of the Imperial Palace. Even though their graves are actually in different locations (the heads involved came from eerily realistic lacquered wood sculptures), an imagined scene of wresting heads off human bodies raises questions about the purpose and permanence of tombs. The structure of the Reikō-den, like the rest of the buildings at Toji, is composed of wood. The temple is situated on sacred ground. Until 1863, the shoguns’ remains were held respectfully through centuries of the many wars and fires that decimated the city. For a Westerner, the idea of a mausoleum made of wood, seems to contradict the very notion of a tomb’s purpose, but it raises the question of how sensible our ideas about funerary architecture really are.

Reiko-den at Toji Temple-Atelier Verde, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

For more details-Keene, Donald (2005). Yoshimasa and the Silver Pavilion: The Creation of the Soul of Japan (Asia Perspectives: History, Society, and Culture). Columbia University Press.

That the Ashikaga were able to construct such a memorial so close to the Emperor’s palace was a clear statement of power, but in 1863 both Kyoto’s long run as the imperial capital and the shogunate itself were at the verge of ending. The city might have been the capital for over a thousand years, but it wasn’t the first. Even its predecessor, Nara, wasn’t the first. And as capitals need to commemorate power, imperial lines need to convey continuity. What better way to serve both needs than with colossal earthworks?

The remains of Japan’s earliest imperial capital, Asuka, are located just south of Nara in the Yamato region. The earliest imperial tombs are tumuli, or kofun, containing the remains of both emperors and empresses and can be found in this area. Dating from the third to seventh centuries, kofun are monumental tumuli of geometrical shape. Most are round (empun), interlocked-rectangular (zenpo koho-fun) or keyhole form (zenpo koen-fun), but squares and even octagons exist. Some scholars consider the royal burial mounds to be a continuation of earlier Yayoi grave practices, others see them as an import from Korea.

Although there are hundreds of Imperial burial mounds, they remain a mystery. The Imperial Household Agency has only on rare occasion allowed any to be analyzed. Very few have been excavated. We know from a small number of examples, like the Ishibutai Burial Mound, that kofun were typically constructed of massive stones that were assembled to form hollow burial chambers and then covered over with enormous quantities of earth.

Ishibutai Kofun-“Ishibutai Tumulus” by D-Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0

As with the more primitive Yayoi burial mounds, many are surrounded by moats. Since the royal kofun have remained undisturbed for so long, they’re typically covered in vegetation and sometimes even by actual woods.

Kofun with moat-“File:Imashirozuka Kofun, zenkei.jpg” by Saigen Jiro is marked with CC0 1.0

For more details-https://en.japantravel.com/nara/japanese-imperial-graves-in-nara/534

With the importation of Buddhism in the mid-sixth century and its doctrines of impermanence which led to cremation practices and the funneling of labor into temple construction, the ruling class eventually stopped constructing tumuli, although the practice continued among commoners to the end of the seventh century. Despite having been desecrated and disturbed from an archaeological perspective, we still have the extraordinary site of Emperor Tenmu’s (d. 686) grave with its lacquer coffin and that of Empress Jito’s (d. 702) cremains, once held in a silver urn, virtually illustrating this transition.

Mausoleum of Tenmu and Jito-Takanuka, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

For more details-http://www.yoshabunko.com/anthropology/Cremation.html

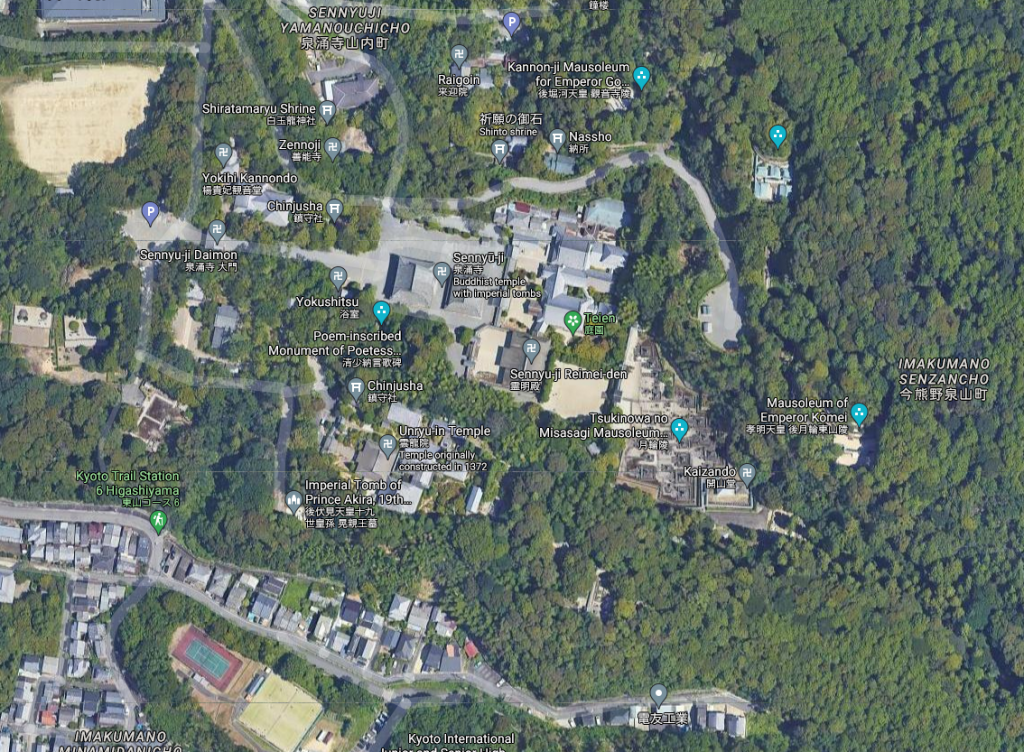

Empress Jito was the first Japanese sovereign to follow the Buddhist practice of cremation, establishing a centuries-long tradition. The ashes of more than a dozen emperors and empresses are memorialized at the Nochi no Tsuki no Wa no Misagi Mausoleum on the grounds of Sennyū-ji Temple in eastern Kyoto. In this case, the mausoleum is a formal wooden barrier with a covered gate that encloses a number of small granite pagodas open to the air in the woods surrounding the temple.

Nochi no Tsuki no Wa no Misagi-Google Maps, Sennyū-ji Temple, Kyoto, Japan, 8/18/21

In 1654, however, Emperor Go-Komyo’s burial interrupted this practice for the first time since the capital had been transferred to Kyoto. The funeral itself followed Buddhist practices, as would those of his successors for another three hundred years. Per the web site JapanVisitor.com, leaving the imperial remains intact “led to sometimes violent reactions by Buddhist monks insisting on cremation, including attempted kidnapping of corpses, but the idea of interment for imperial bodies prevailed.”

For more details-https://www.japanvisitor.com/japanese-history/musashi-imperial-graves

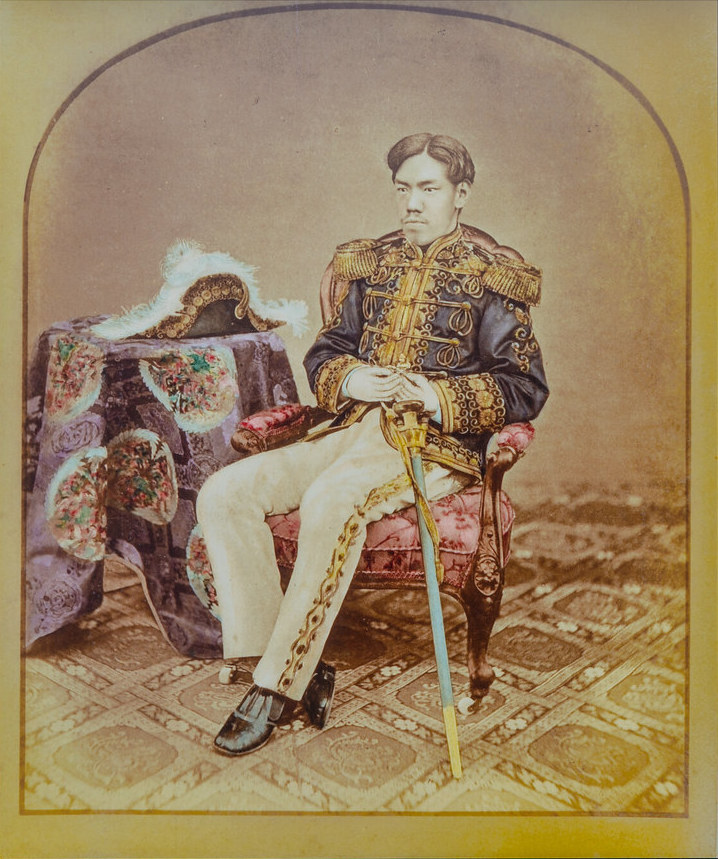

Little by little, the practice of constructing kofun over the body of the emperor came back into favor. Emperor Meiji’s father, Komei, the last Edo Period sovereign, was laid to rest under a burial mound at Sennyū-ji. Two other Edo Period emperors have similar memorials there. It is with the Meiji restoration that the practice returns to regular use, although Emperor Meiji himself is the last emperor to be buried at Kyoto. Having returned to Shinto practices due to the cataclysmic political changes following the collapse of the shogunate, his grave stands apart at Fushimi Momoyama to the south. The Emperors following him are interred under tiered burial mounds at Musashi Imperial Cemetery. This site is a charming, forested area in Hachioji, west of Tokyo.

Emperor Meiji-“Emperor Meiji, 1873” by FlickrDelusions is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In order to minimize environmental impact, Retired Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko have decided to be cremated, which would break with the tradition resumed by Go-Komyo. The retired emperor initially intended for his consort to be entombed with him, but the empress demurred, perhaps due to her non-aristocratic pedigree. Their cremains will be housed in separate “mausolea,” by which is meant circular tiered burial mounds on square earthen bases. As the couple tend to view themselves as relatively modest, these constructions will be approximately eighty percent of the size of other imperial memorials at Musashi, to permit more space for future sovereigns.

For more details-http://www.asianews.it/news-en/Revolution-in-Tokyo:-Emperor,-Empress-to-be-cremated-and-buried-in-eco-friendly-mausoleums-29550.html

Musashi Imperial Cemetery-Staka, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

For more details-https://www.japanvisitor.com/japanese-history/musashi-imperial-graves

The Shoguns following the Ashikaga erected Gorin-to pagodas similar to those of the imperial memorials at Sennyū-ji, although attitudes about cremation vs. burial shifted over the course of the shogunate. Tokugawa Ieyasu, having betrayed Hideyori, followed Toyotomi Hideyoshi as ruler of the country, assuming the official title of Shogun. It is perhaps for this reason that he inserts a sculpture of himself among those of the Ashikagas within the mausoleum chamber of the Reikō-den. He elides past the Oda whose pedigree, like Hideyoshi’s, rendered them ineligible to be shogun, although they too had ruled the country. His presence at Toji suggests that Tokugawa wished to link himself to the Ashikaga clan and give an impression of continuity between the two dynasties.

Ieyasu, having put an end to the possibility of a Toyotomi shogunate, in the end is credited as being the last of the great unifiers of Japan. It was he who separated the imperial capital at Kyoto from the administrative one at Edo, ultimately leading to the transfer of the emperor to Tokyo in the nineteenth century. It’s well-known that his spirit is memorialized at the grand complex of Nikko Toshogu in Tochigi Prefecture, but few realize that he chose his remains to be interred on a mountaintop with a modest pagoda much like the one commemorating his predecessor. This can be found at the top of Mt. Kunou.

Ieyasu’s gravesite-“Tokugawa Ieyasu’s grave (御宝塔, gohōtō)” by foliosus is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Even less known is that Hideyoshi’s remains were laid to rest on Mt. Amidagamine outside of Kyoto. His successor ultimately set the stage for his legacy to be destroyed. At Ieyasu’s behest, Hideyoshi’s grave complex of Shinto shrine, Buddhist temple and grave site were dismantled between 1615 and 1619, but it seems the grave itself was left in place, even if its marker was removed. With the Meiji Restoration an extensive memorial to Hideyoshi was reconstructed. Today there is a monumental granite Gorin-to marker at the head of a flight of 500 steps which commemorates his remains.

Mt. Amidagamine-“Hokoku-byo: Steps to Hideyoshi’s Grave” by jpellgen (@1179_jp) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

For more details-https://www.kyoto-museums.jp/en/museum/east/3876/

For more details-https://factsanddetails.com/japan/cat25/sub165/entry-6573.html

The most ephemeral mausoleum of all is to be found at Kodaiji Temple in Kyoto. The Otama-ya commemorates both Hideoyoshi and his consort, Kita-no-Mandokoro (known as Nene), founder of the temple, whose grave it marks. The mausoleum houses memorial sculptures of the couple in grand enclosed niches, Nene in her nun’s habit, Hideyoshi in his armor. Visitors in early November may be lucky enough to see them during the brief period of the year when the mausoleum is open for viewing. It’s said that despite the scourge of fire that destroyed so many of Kyoto’s treasures over the centuries, the Otama-ya is the original construction from the early seventeenth century. This would be miraculous since the entire structure, the stairs leading up to it and the altar, including the black and gold panels that conceal the memorial sculptures, are entirely constructed of Kōdai-ji maki-e, for which the temple is famous. A brittle, shiny finish laid layer upon layer over a fragile wood base, Kodaiji maki-e is the most elegant of all lacquerware.

Otama-ya-“Kyōto – Higashiyama: Kōdai-ji – Otama-ya” by wallyg is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

For more details-https://www.discoverkyoto.com/places-go/kodai-ji/

Corrections were made to the first two paragraphs on 2/15/22 clarifying that the Reikō-den did not house the remains of the shoguns, only their life-sized effigies.